Cleveland Clinic Integrative Health Learning Collaborative Case

The Integrative Health Learning Collaborative sought to improve the delivery of whole-person care and make integrative health routine and regular in primary care. During the learning collaborative, the Cleveland Clinic Family Medicine Residency Program made integrative health tools and visits part of standard residency training and annual physicals at the Lakewood Family Health Center.

Introduction

[ultimate_heading main_heading=”THE BURDEN OF CHRONIC DISEASE” heading_tag=”h3″ main_heading_color=”#0f6378″ alignment=”left” main_heading_style=”font-style:italic;,font-weight:bold;” main_heading_font_size=”desktop:20px;” main_heading_margin=”margin-bottom:20px;”][/ultimate_heading]Six in 10 adults in the U.S. have at least one chronic disease, and four in 10 have two or more, according to the CDC.1 People in underserved communities bear far more of the burden of chronic disease than people in more affluent communities.

The COVID-19 pandemic emphasized these health and health care disparities. More people in underserved communities, especially those from racial and ethnic minority groups, got sick or dyed or were at higher risk of getting sick and dying from COVID-19 compared to the general population.

Even before the pandemic, primary care providers struggled to find the time, tools and resources to help patients with chronic diseases—whether affluent or underserved—improve their health and wellbeing. Yet, most chronic diseases seen in primary care can be prevented, managed or even reversed by addressing their underlying social and behavioral determinants.

BETTER WAY TO MANAGE CHRONIC DISEASE

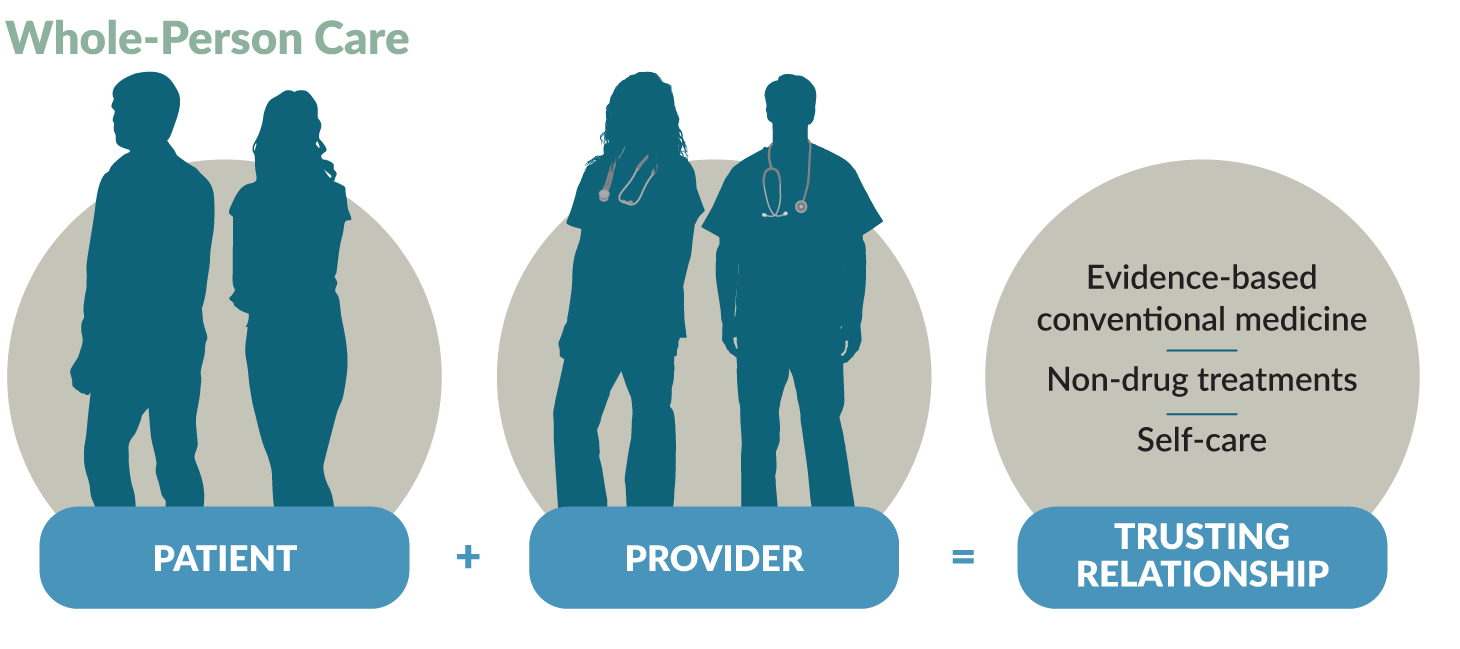

Whole-person care and integrative health focus on helping patients achieve health and wellbeing, not just on the treatment of disease, illness and injury. It is a better way to manage chronic disease because it addresses all the factors that impact health and healing:

- Medical treatment

- Mental health

- Personal behaviors and lifestyle

- Social determinants of health

- Personal determinants of healing

Integrative primary care providers use all proven approaches:

- Evidence-based conventional medicine

- Non-drug treatments (including complementary and alternative medicine)

- Self-care

They focus on what matters most to each person and establish trusting, ongoing relationships to help patients heal.

Whole-Person Care

Helps patients achieve health and wellbeing:

Integrative primary care providers use a person-centered, relationship-based approach to integrate self-care with evidence-based conventional medicine and non-drug treatments. They consider all factors that influence healing:

- Medical treatment

- Mental health

- Personal behaviors and lifestyle

- Social determinants of health

- Personal determinants of healing

Uses proven approaches:

Integrative primary care providers coordinate the delivery of evidence-based conventional medicine and non-drug treatments and self-care:

- Conventional medicine is the delivery of evidence-based approaches for disease prevention and treatment currently taught, delivered and paid for by the mainstream health care system.

- Non-drug treatments focus on non-pharmacological approaches to care and include what is sometimes called complementary and alternative medicine (CAM).

- Self-care is all the evidence-based approaches that individuals can engage in to care for their own health and wellbeing. Self-care promotes healthy behaviors and a healthy lifestyle to enhance health and healing. Approaches focus on the connection between the body, the mind the spirit and behavior, and cover food, movement, sleep, stress, substance use and more. Improving one area can influence the others and benefit overall health.

Goes beyond the doctor’s office to consider context:

Whole-person care is framed by each person’s social and personal context:

- Social determinants of health are the conditions in the places where people live, learn, work and play that affect health and quality of life.

- Personal determinants of healing are those personal factors which influence and promote health and healing. These include the physical, environmental, lifestyle, social, emotional, mental and spiritual dimensions which are connected and must be balanced for a happy and fulfilled life.

- Health Coaching is a delivery method for whole-person care. Health coaches use their expertise in human behavior to help individuals set and achieve health goals. They are an increasingly important component of whole-person care teams.

Providers work with patients to create a personalized health plan based on the person’s needs and preferences. To do this, they use free tools such as:

- The PHI (Personal Health Inventory), which assesses the person’s meaning and purpose in life, current health and readiness for change. Patients complete this before or during a primary care visit that integrates health and wellbeing.

- The HOPE (Healing Oriented Practices & Environments) Note, a patient-guided process to identify the person’s values and goals in life and for healing so the provider can assist them in meeting those goals with evidence and other support.

Whole-Person Care Works

Evidence shows that whole-person care is effective in meeting the quadruple aim of:

- Better outcomes

- Improved patient experience

- Lower costs

- Improved clinician experience

Read more about the evidence supporting whole-person care.

THE INTEGRATIVE HEALTH LEARNING COLLABORATIVE

The Integrative Health Learning Collaborative sought to better manage chronic disease by addressing social and behavioral determinants of health to:

- Improve the delivery of whole-person care

- Make integrative health routine and regular in primary care

Seventeen clinics participated in the learning collaborative, held from October 2020 to September 2021. The Family Medicine Education Consortium and Samueli Integrative Health Programs sponsored the learning collaborative, which was funded by a grant from The Samueli Foundation.

Read more about the Integrative Health Learning Collaborative.

THE CHALLEGNE

[ultimate_heading main_heading=”STRENGTHENING INTEGRATIVE HEALTH IN PRIMARY CARE” heading_tag=”h3″ main_heading_color=”#0f6378″ alignment=”left” main_heading_style=”font-style:italic;,font-weight:bold;” main_heading_font_size=”desktop:20px;” main_heading_margin=”margin-bottom:20px;”][/ultimate_heading]Cleveland Clinic is a nonprofit multispecialty academic medical center that integrates clinical and hospital care with research and education. The 6,000-bed health system includes:

- A 173-acre main campus near downtown Cleveland

- 19 hospitals

- More than 220 outpatient facilities.

Services are also available in southeast Florida; Las Vegas, Nevada; Toronto, Canada; Abu Dhabi, Unite Arab Emirates; and London, England.

Cleveland Clinic has 68,700 employees worldwide, including more than 4,600 salaried physicians and researchers and 17,400 registered nurses and advanced practice providers. These clinicians represent 140 medical specialties and subspecialties. In 2020, the Cleveland Clinic health system had 8.7 million outpatient visits, 273,000 hospital admissions and observations and 217,000 surgical cases.

Cleveland Clinic is committed to undergraduate and graduate medical education. The Graduate Medical Education program is one of the largest in the country. In 2021, Cleveland Clinic trained more than 1,850 residents and fellows.

THE CLEVELAND CLINIC FAMILY MEDICINE RESIDENCY PROGRAM

The Lakewood Family Health Center, the clinical practice for the Cleveland Clinic Family Medicine Residency Program, serves a young and diverse population, including many immigrants. Patients span all ages and all socioeconomic backgrounds. Twenty resident physicians, 7 physician faculty and 2 nurse practitioners serve about 1,475 patients per month.

The Cleveland Clinic Family Medicine Residency Program has been using integrative health to address the social and behavioral determinants of health and provide better care to patients for many years. Carl Tyler Jr., MD, the Geriatrics and Research Curriculum Director for the family medicine residency program, is a long-time practitioner of whole-person care and integrative health. He is a champion of integrative health in Cleveland Clinic’s Family Medicine Residency Program.

“Integrative health is intrinsic to the nature of family medicine in its purest form and how people attracted to family medicine tend to think.”

“We tend to think holistically and be open to alternative ways of preventing and treating disease,” says Dr. Tyler. “We listen to patient insights. We serve as consultants, collaborators and coaches to our patients.”

Also, integrative health helps alleviate “the deficits of how health care is often practiced and the ills of the system,” he says. Integrative health enables physicians to better manage pain and chronic conditions and provide preventive healthcare.

Cleveland Clinic’s Family Medicine Residency Program offers all residents the opportunity to participate in the University of Arizona online Integrative Medicine in Residency program. This 200-hour competency based, interactive, online curriculum in integrative medicine is designed for incorporation into primary care residency education.

“Most of our residents participate in this program. It’s a reason they choose our residency program,” says Jessica C. Tomazic, MD, a third-year family medicine resident at Cleveland Clinic. Residents also present what they are learning to other residents.

While the Cleveland Clinic Family Medicine Residency Program was already addressing social and behavioral determinants of health, leaders joined the Integrative Health Learning Collaborative to learn how to:

- Better organize and deliver integrative health services

- Increase the volume of integrative health services at the clinic

WORK DURING THE INTEGRATIVE HEALTH LEARNING COLLABORATIVE

[ultimate_heading main_heading=”BUILDING AN INTEGRATIVE HEALTH STRUCTURE AND SYSTEM” heading_tag=”h3″ main_heading_color=”#0f6378″ alignment=”left” main_heading_style=”font-style:italic;,font-weight:bold;” main_heading_font_size=”desktop:20px;” main_heading_margin=”margin-bottom:20px;”][/ultimate_heading]During the Integrative Health Learning Collaborative, the Cleveland Clinic Family Medicine Residency Program trained more residents in integrative health, changed the workflow to facilitate integrative heath and studied the results in an IRB-approved research study.

THE INTEGRATIVE HEALTH TEAM

The Integrative Health Learning Collaborative project was led by residents at the Cleveland Clinic Family Medicine Residency Program, with support from faculty. Stephanie Deuley, MD, was the initial lead resident. When she completed her training, Dr. Tomazic assumed her role. The faculty lead for the project was initially Robert B. Kelly, MD, MS. When Dr. Kelly left Cleveland Clinic, Dr. Tyler assumed the role of faculty lead.

The full team was comprised of:

- Five residents, with representatives of each class

- Three faculty members

- A behavioral science coordinator who created the behavior change curriculum that is the foundation for the project

- A nurse educator who developed resources and acted as a health coach (she left Cleveland Clinic during the project)

- A nursing leader who helped staff implement the changes

- A research assistant

Weekly meetings with providers and staff helped obtain buy-in for the project and helped the integrative health team advance the project and monitor progress.

Patient Case: Developing a Plan to Relieve Stress and Reduce Blood Pressure

Lindsey (not her real name) lives a fairly healthy lifestyle. She is an active climber and yoga practitioner, and a vegan. Yet, she had hypertension that lisinopril didn’t adequately control. Lindsey also had anxiety and depression, which often led to significant stress in her life despite treatment with paroxetine.

When the 56-year-old woman went to the Lakewood Family Health Center for her annual physical exam in 2021, she completed the PHI and the PROMIS-10 and then saw Dr. Tomazic. After reviewing the paperwork and talking with Lindsey, Dr. Tomazic suggested a HOPE visit. “Lindsey felt ‘bad’ about having to use medication to treat her high blood pressure despite a relatively healthy lifestyle. She wished to try alternative means to help lower her blood pressure without increasing or adding medication,” says Dr. Tomazic.

Based on Lindsey’s PHI, Dr. Tomazic focused on stress management with her. “We could strategically use stress management to concurrently address her high blood pressure, which remained mildly elevated in the office despite medical treatment, and her anxiety and depression,” says Dr. Tomazic.

Dr. Tomazic explored Lindsey’s perceptions of and experience with meditation. Lindsey had previously meditated but had stopped several years earlier when she started feeling better. Then excess stress slowly began creeping back into Lindsey’s life.

They discussed how meditation can help control blood pressure and balance the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems, and their impact on the stress and biophysical responses. Lindsey agreed to start meditating again, however, with a busy work and social schedule, she didn’t have much time for this. Together, Dr. Tomazic and Lindsey set an attainable goal for meditating, starting with a 5-minute practice three times a week in the morning before work.

EVALUATING WHOLE-PERSON CARE

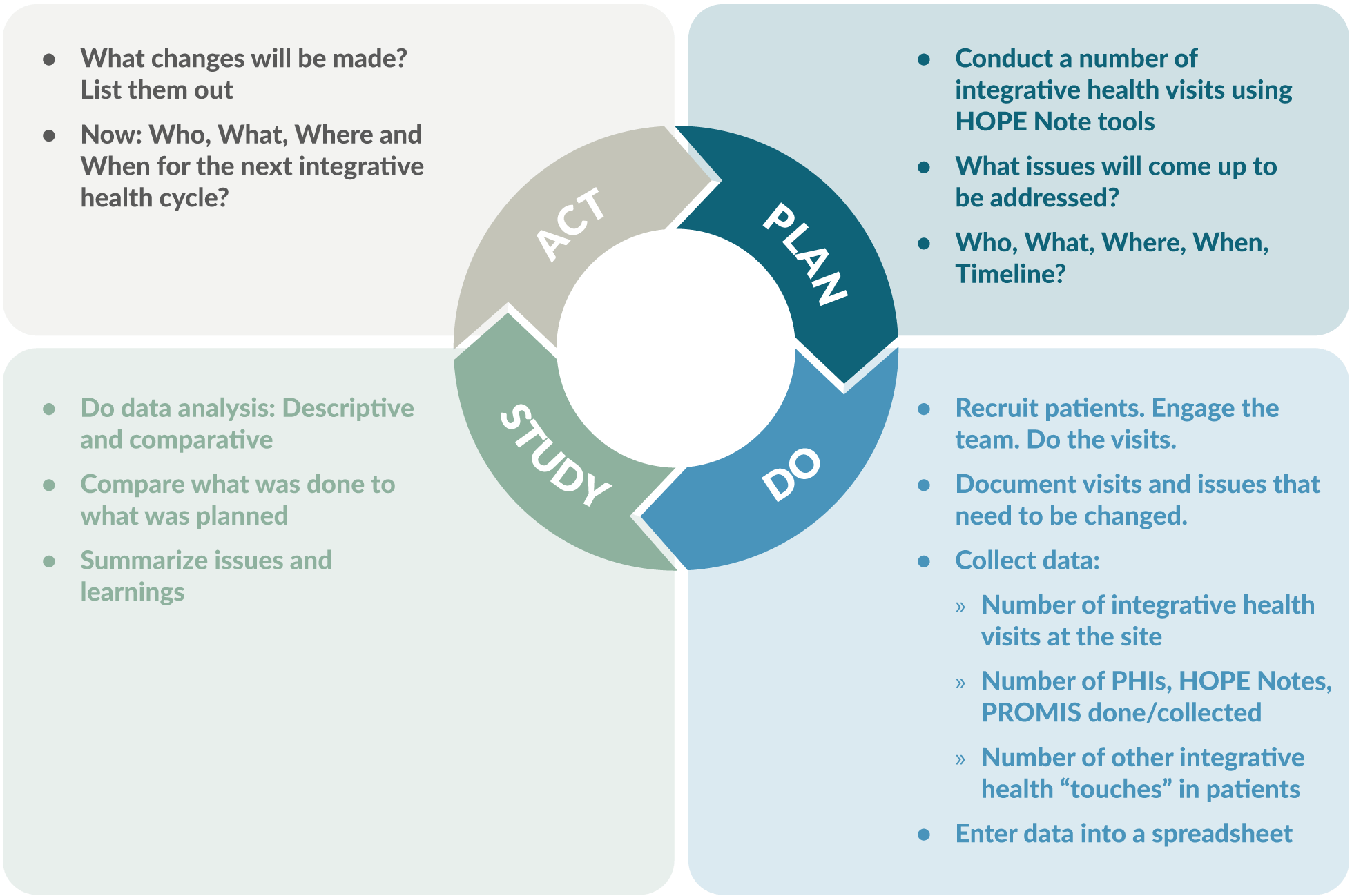

The Cleveland Clinic Family Medicine Residency Program evaluated its use of integrative health for practice and clinical improvement. They used the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle and the McKinsey 7S model of change management to plan and manage implementation and to evaluate their changes and plan next steps to expand the delivery of integrative health.

Read more about PDSA cycles and the McKinsey 7S model of change management.

Here is what the Cleveland Clinic Family Medicine Residency Program did.

The project team at the Cleveland Clinic Family Medicine Residency Program went well beyond the requirements of the Integrative Health Learning Collaborative and conducted a formal research study to track implementation of integrative health practices in primary care. The study had two aims:

- Aim 1: To increase the number of integrative health discussions occurring during routine clinical encounters in the Lakewood Family Health Center.

- Aim 2: To document the impact of these integrative health discussions on self-rated health and function in patients.

Dr. Tyler worked with the IRB to obtain approval for the study protocol. This was a complex and lengthy process that required about 30 revisions and an informed consent form for patients who agreed to participate. The delays were due to the priority given to COVID-19 research projects.

Researchers collected the following data:

PHI:

- Number of intake forms documented, with a goal of two per patient (initial and follow-up)

HOPE Note:

- Number of integrative health discussions documented in a HOPE Note

PROMIS-10:

- Change in this assessment of self-rated health and functional status over a six-month period. Patients at Cleveland Clinic often submit the PROMIS-10 via MyChart before appointments as a routine part of their primary care.

Healthy Days:

- Change in the number of healthy days within the last 30 days assessed over a six-month period.

Providers recruited more than 50 patients, meeting their goal, to participate in the study. As of February 2021, they were still collecting data.

KEY RESULTS

[ultimate_heading main_heading=”MAKING INTEGRATIVE HEALTH TOOLS AND VISITS STANDARD” heading_tag=”h3″ main_heading_color=”#0f6378″ alignment=”left” main_heading_style=”font-style:italic;,font-weight:bold;” main_heading_font_size=”desktop:20px;” main_heading_margin=”margin-bottom:20px;”][/ultimate_heading]CLINIC HIGHLIGHTS

The Cleveland Clinic Family Medicine Residency Program reported the following accomplishments related to integrative health.

Integrative health tools (PHI and HOPE Note) and visits are now part of standard family medicine residency training and competencies.

The integrative health team trained residents, as well as faculty and staff, in integrative health, including use of the PHI and HOPE Note, and set up processes to facilitate the teaching and use of integrative health. Each person completed their own PHI to understand the process and the tool.

Residents led training for other residents, from interns to third-year residents. Training included:

- A three-hour education session with second-year interns on why and how to conduct a HOPE visit during the Health Promotion block rotation

- Several education sessions at lunchtime all-staff meetings

- Co-counseling visits by each resident with the behavioral science director

“What better opportunity to impact practice then when residents are learning

how to practice?”

Family medicine residents enjoy using integrative health to care for their patients and training them at the beginning of their career has the potential to impact patients’ health more broadly. “To make whole-person health and integrative health a part of the dialogue from early on in their training will stick for years to come,” says Dr. Tomazic. As residents move on to other clinics, they can use their integrative health training and tools to continue to provide whole-person care for their patients in any specialty.

Faculty and staff from schedulers to medical assistants also received training in integrative health. The assistant nurse manager conducted an education session for support staff.

Getting buy-in from faculty has been difficult as it’s difficult to change long-established practice patterns. The integrative health team continues to provide training in integrative health and to discuss it at faculty and all-staff meetings.

Integrative health is now part of annual physicals at the Lakewood Family Health Center.

At annual physicals, all providers ask questions related to integrative health developed by the integrative health team. They also have the option to complete the PHI and PROMIS-10 with patients and to conduct a HOPE visit if they think the patient will benefit from this.

For the study, the integrative health team added to the annual physical packets an enrollment packet (PHI, PROMIS-10 and informed consent form) with a cover page describing the project. This made it easy for providers to enroll patients in the study and will make it easier for them to continue to do integrative health visits. Also, every exam room has scheduling tickets and a sign about HOPE visits.

Providers do routine follow-up with patients two weeks after the HOPE visit through MyChart and schedule another visit a few weeks after that. They also use Cleveland Clinic’s e-coaching services, where health coaches provide advice based on the patient’s medical record and the provider’s notes.

“When making big changes, having somebody check in with you more often can be really beneficial. Some people like the accountability and having somebody to strategize with,” says Dr. Tomazic.

“Patients appreciate that we care about what matters to them and want to know

them in a meaningful way”

Residents and faculty developed skills in assessing integrative health needs and motivating patients to achieve health and well-being by discussing what matters most to them and their health goals. Many patients were very receptive to integrative health, which empowers patients to participate in their care. They liked having more time with the provider and learning about how what is happening in their lives impacts their health. Also, many patients are looking for alternatives to taking more drugs.

Workflow changes are facilitating the use of integrative health by more providers.

The workflow for conducting and tracking integrative health visits includes scheduling tickets and tools in Epic. The scheduling tickets, placed in all exam rooms, make it easy for providers to do integrative health visits with patients.

The Scheduling Ticket for an Integrative Health Visit.

The integrative health team created tools in Epic such as a HOPE Note template and an express lane that aligns resources with the care provided during HOPE visits. For example, providers can easily access referrals to acupuncture and other services provided outside of Cleveland Clinic.

Residents and other providers use the HOPE Note and the HOPE visit to structure behavior change discussions and identify patients who need more help.

The HOPE Note and HOPE visit provide a structure, especially for residents, to talk about behavior change and use the Cleveland Clinic Family Medicine Residency Program’s behavior change curriculum. “Patients seem to get it quickly and really appreciate the time and the depth of inquiry that it leads to,” says Dr. Tyler.

“The HOPE Note and visit get patients and physicians thinking in different ways than the usually reductionist thinking we often get into with brief visits that are focused on problems.”

Also, using the HOPE Note enables providers to identify patients who might benefit from more focused work with integrative or functional medicine. Providers can then make referrals to these specialists within Cleveland Clinic.

Providers discovered, however, that follow-up for a HOPE visit after filling out a PHI was low and some patients were not ready for a HOPE visit. Also, insurance restrictions are sometimes a barrier to follow-up visits.

Now that integrative health is part of annual physicals, Dr. Tomazic expects patient interest to grow as providers discuss integrative health each year. She noted that in general, it takes 10 to 12 touches with the health care system before many patients establish behavior change.

“While they may not be ready for an integrative health visit initially, as they hear more about it, it might start to resonate with them,” she says.

LEARNING COLLABORATIVE HIGHLIGHTS

The Cleveland Clinic Family Medicine Residency Program reported the following benefits of participating in the Integrative Health Learning Collaborative.

Being part of the learning collaborative enabled the team to take integrative health in the Cleveland Clinic Family Medicine Residency Program to the next level.

“Participating in the learning collaborative allowed us to make integrative health a more natural part of our daily work, not an add on.”

Integrative health is now part of standard residency training and annual physicals at the Lakewood Family Health Center.

Collaborating with other clinics facilitated the use of Epic to make it easier for providers to use integrative health.

The Cleveland Clinic Family Medicine Residency Program worked with the Susan Samueli Integrative Health Institute at UCI and Jamaica Hospital Medical Center, two other clinics participating in the Integrative Health Learning Collaborative, to create integrative health tools in Epic, their electronic health record system. Information technology staff at Cleveland Clinic met with their peers at Jamaica Hospital Medical Center to learn how Epic was being used there for integrative health visits.

Learning from other clinics sparked ideas for integrative health at the Cleveland Clinic Family Medicine Residency Program.

Learning collaborative meetings included presentations by participating clinics on their work in integrative health and small group discussions of ways to meet challenges. Also, participating clinics shared their resources on Google Drive. Learning about what the other clinics were doing and accessing their resources helped the integrative health project team at the Cleveland Clinic Family Medicine Residency Program improve the use of and workflow for integrative health.

Gaining momentum and motivation helped the integrative health team continue to make progress and solve problems.

“Taking part in the Integrative Health Learning Collaborative allowed us to dedicate time to encouraging and promoting health in our patients and proved to be a very uplifting and educational experience for both patients and residents”

Being part of the Integrative Health Learning Collaborative provided dedicated time to work on integrative health and momentum for the group. Learning about what other clinics were doing provided ideas and motivation to keep working on the project. “Connecting with people who have similar passion helps sustain passion,” says Dr. Tyler.

Key Insights for Implementing Integrative Health

Family medicine residency programs are a great way to introduce or expand integrative health. Residents do not have established practice patterns and are open to learning about and using integrative health. As they take their integrative health training and experience with them to other practice settings, there is strong potential to make integrative health routine and regular in primary care.

Family medicine residency programs can provide formal training in integrative health as the Cleveland Clinic did. Training methods include:

- The University of Arizona online Integrative Medicine in Residency program

- Education sessions for residents including didactic lectures and lunch and learn training

- Resident presentations to other residents on integrative health

Consider formal training for residents through the University of Arizona online Integrative Medicine in Residency program. This 200-hour competency-based, interactive, online curriculum in integrative medicine is designed for incorporation into primary care residency education.

Find an integrative health champion. Making integrative health routine and regular in primary care requires having a champion who will take the lead and continually make integrative health a part of clinic policies, procedures and discussions. Dr. Tyler was the primary faculty champion for this project. Dr. Deuley and then Dr. Tomazic were the project champions among the residents.

Both resident and faculty champions were essential to the success of this project. Additionally, the residency program director provided administrative support for key residents to attend Integrative Health Learning Collaborative meetings and approved institutional financial support for key participants to attend a Family Medicine Education Consortium meeting.

Persistence is key in making practice changes such as making integrative health routine and regular in primary care. Consistent, repeated education of residents, faculty and staff and ongoing promotion of integrative health visits in exam rooms to patients and providers facilitated the more widespread adoption of integrative health at the Cleveland Clinic Lakeview Family Health Center.

Make it easy for providers to use integrative health. Cleveland Clinic Family Medicine Program made it easy for residents and other providers to do integrative health visits and refer patients for services by providing questions to ask, packets with key information and scheduling tickets for integrative health visits. Also, the team added the HOPE Note template and integrative health referral resources to Epic.

Get buy-in from staff. The integrative health team made presentations and led training on integrative health to faculty, nurses, medical assistants and other staff. The team discussed integrative health repeatedly at faculty and staff meetings. Having staff complete the PHI also helped them understand integrative health.

Make integrative health part of your routine process. The Cleveland Clinic Family Medicine Program integrated the PHI with routine exams and preventive health. This is much easier and more effective than trying to do a separate visit for the PHI. If a patient decides to then do a HOPE visit, this should be a separate visit.

CHALLENGES

[ultimate_heading main_heading=”GETTING BUY-IN AND LOSING FACULTY AND STAFF” heading_tag=”h3″ main_heading_color=”#0f6378″ alignment=”left” main_heading_style=”font-style:italic;,font-weight:bold;” main_heading_font_size=”desktop:20px;” main_heading_margin=”margin-bottom:20px;”][/ultimate_heading]Getting buy-in from faculty has been difficult. Changing long-established practice patterns is difficult. The integrative health team is trying to do this by providing ongoing training in integrative health and raising awareness of integrative health at meetings.

Losing key faculty and staff slowed progress. The initial faculty champion and several key staff members left the Cleveland Clinic during this project. This slowed the adoption of integrative health and completion of the research project. COVID-19 has exacerbated this turnover.

NEXT STEPS

[ultimate_heading main_heading=”SPREADING THE USE OF INTEGRATIVE HEALTH” heading_tag=”h3″ main_heading_color=”#0f6378″ alignment=”left” main_heading_style=”font-style:italic;,font-weight:bold;” main_heading_font_size=”desktop:20px;” main_heading_margin=”margin-bottom:20px;”][/ultimate_heading]The integrative health team plans to continue to encourage the use of integrative health by family medicine residents and faculty at the Cleveland Clinic Lakeview Family Health Center, and to continue to educate faculty about integrative health. In addition, the medical school at the Cleveland Clinic is interested in starting to train medical students in integrative health and the HOPE tools.

Dr. Tomazic’s goal is for all primary care clinics at Cleveland Clinic to be aware of and know how to use integrative health, so that it becomes routine and regular in primary care.

Integrative health tools may also be used in shared medical appointments, also called group visits, led by third-year residents. The integrative health team is exploring ways to do this.

The integrative health team will analyze the results of the research study to track implementation of integrative health practices at the Cleveland Clinic Lakeview Family Health Center and develop a plan for sharing the results.

APPENDIX 1

[ultimate_heading main_heading=”EVIDENCE SUPPORTING WHOLE-PERSON CARE” heading_tag=”h3″ main_heading_color=”#0f6378″ alignment=”left” main_heading_style=”font-style:italic;,font-weight:bold;” main_heading_font_size=”desktop:20px;” main_heading_margin=”margin-bottom:20px;”][/ultimate_heading]Evidence from existing whole-person care supports the effectiveness of this model in meeting the quadruple aim:

- Better Outcomes

- Improved Patient Experience

- Lower Costs

- Improved Clinician Experience.

This evidence includes a narrative review of several models of whole-person care and studies illustrate the business case for whole-person models in primary care2 and the models and studies cited in this section.

BETTER OUTCOMES

Whole-person care:

- Increases the ability to manage chronic pain and decreases opioid doses.3

- Improves patient-reported health and wellbeing.4

- Lowers A1c in people with diabetes.5

- Improves medication adherence.6

- Facilitates a healthier lifestyle.7

- Reduces the severity of heart disease.8, 9

- Reduces loneliness among seniors.10

- Lessens symptoms, including pain, depression, low back pain and headaches.11, 12, 13

IMPROVED PATIENT EXPERIENCE

Whole-person care:

LOWER COSTS

IMPROVED CLINICIAN EXPERIENCE

APPENDIX 2

[ultimate_heading main_heading=”PDSA CYCLES AND THE MCKINSEY 7S MODEL OF CHANGE MANAGEMENT” heading_tag=”h3″ main_heading_color=”#0f6378″ alignment=”left” main_heading_style=”font-style:italic;,font-weight:bold;” main_heading_font_size=”desktop:20px;” main_heading_margin=”margin-bottom:20px;”][/ultimate_heading]THE PDSA CYCLE

The PDSA cycle is a tool for documenting change. Clinics participating in the Integrative Health Learning Collaborative planned and tested small changes, learned from the results, and modified the changes as necessary.

PDSA Cycle

Source: Slide 9, PDSA and 7S Report Outs v1

THE MCKINSEY 7S MODEL OF CHANGE MANAGEMENT

The McKinsey 7S model of change management is a good way to plan and manage implementation of integrative health. The model considers three structural elements: strategy, systems and structure. It also recognizes three “people” elements needed to win the hearts of everyone from front office staff

to the most senior physicians. These include addressing the types of people who are going to lead the change, the skills of the people who will be involved, and the overarching leadership style within the organization. These elements are fuzzier, more intangible, are influenced by corporate culture and are sometimes more difficult to address.

The McKinsey 7S Model of Change Management

Graphic CC-BY 2.5 Wikimedia

Managing change by addressing all these barriers leads to the 7th “S,” creation of shared values underpinning the culture of the group.

Structural and People Elements in the McKinsey 7S Model of Change Management

[su_table responsive=”yes” class=”custom-su-table”]

| Structural Elements: | |

|---|---|

| Strategy: | What do you want to do differently? What will it replace? |

| Systems: | What changes in workflow needs to happen to do the new thing? |

| Structure: | How are you going to set up a new system to kick off and then monitor the initiative? |

| People Elements: | |

| Style: | How are you going to lead the change? |

| Staff: | Who can you enlist who will make it happen? Who do others in your practice look to for guidance? |

| Skills: | Who needs to be trained in the new workflow? What is the training? How can you give them ownership? |

[/su_table]

Addressing all these issues through careful planning will lead to development of the shared values, the commonly accepted standards and norms within the practice that will make the switch to whole-person care a success.

USING THE 7S MODEL TO PLAN IMPLEMENTATION

Substantial planning is necessary to make the change to whole-person care.

Strategy: The obvious changes, as part of this initiative, are to start using the PHI, start conducting integrative visits around the HOPE note, and start setting up a way to monitor both your implementation and the outcomes you’ve settled on. Who is going to do what?

Systems: Careful attention is needed to identify new systems to support whole-person care. Most aspects of the practice will need to be changed in some way, including front-office, billing, and clinical care workflows. Having a Plan B on the shelf will be useful.

Structure: Determine how the roll-out will occur. It may be best to start a pilot project with a single team, carefully chosen for their ability to embrace change. Their success must be carefully monitored so that processes can change when barriers are discovered.

Style: Decide on whether the change to whole-person care will be incremental or dramatic. Decide on who will lead the implementation and how they will approach it. Develop a means of getting staff members excited. Decide how much input the staff will have in the implementation. Set up a rapid cycle quality improvement plan.

Staff: You will need to enlist key people to make your implementations happen and to make it stick. These may be people in key roles, but you will need to identify an opinion leader and a first follower (the first person in the organization to support the opinion leader) for the implementation to be widely adopted.

Skills: Whole-person care requires a new set of skills and new practices. Identify who will need to receive new training and determine how to provide the training.

The McKinsey model is probably well known to most hospital administrators but less known to clinicians and managers. Soon a five-part continuing medical education series for clinicians, staff and managers will be available that explains the HOPE note and introduces integrative health to the team and managing and monitoring the implementation process.

ENDNOTES

- Chronic Disease in America. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/tools/infographics.htm. Accessed 10/25/21.

- Jonas, W, Rosenbaum E. The Case for Whole-Person Integrative Care. Medicina. 30 June 2021. https://www.mdpi.com/1648-9144/57/7/677/htm. Accessed 11/8/21.

- Bokhour BG, Hyde J, Zeliadt S, Mohr H. Whole Health System of Care Evaluation – A Progress Report on Outcomes of the WHS Pilot at 18 Flagship Sites. February 18, 2020. Veterans Health Administration, Center for Evaluating Patient-Centered Care in VA (EPCC-VA). https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/docs/EPCC_WHSevaluation_FinalReport_508.pdf. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Crocker R, Hurwitz JT, Grizzle AJ, et al. Real-World Evidence from the Integrative Medicine Primary Care Trial (IMPACT): Assessing Patient-Reported Outcomes at Baseline and 12-Month Follow-Up. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2019, Article ID 8595409. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/8595409. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Hojat M, Louis DZ, Markham FW, Wender R, Rabinowitz C, Gonnella JS. Physicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. AcadMed. 2011 Mar;86(3):359-64. doi: 10.1097/ ACM.0b013e3182086fe1. PMID: 21248604. https://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine/Fulltext/2011/03000/Physicians__Empathy_and_Clinical_Outcomes_for.26.aspx. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Zolnierek KB, Dimatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009 Aug;47(8):826-34. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5acc. PMID: 19584762; PMCID: PMC2728700. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19584762/. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Budzowski AR, Parkinson MD, Silfee VJ. An Evaluation of Lifestyle Health Coaching Programs Using Trained Health Coaches and Evidence-Based Curricula at 6 Months Over 6 Years. Am J Health Promot. 2019 Jul;33(6):912-915. doi: 10.1177/0890117118824252. Epub 2019 Jan 22. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30669850/. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, at al. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet Supplemented with Extra-Virgin Olive Oil or Nuts. N Engl J Med 2018; 378:e34. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800389. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1800389. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Ornish D, Scherwitz LW, Billings JH, et al. Intensive Lifestyle Changes for Reversal of Coronary Heart Disease. JAMA, December 16, 1998—Vol 280, No. 23. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9863851/. Abstract accessed 7/15/21.

- Thomas KS, Akobundu U, Dosa D. More Than A Meal? A Randomized Control Trial Comparing the Effects of Home-Delivered Meals Programs on Participants’ Feelings of Loneliness. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2016 Nov;71(6):1049-1058. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbv111. Epub 2015 Nov 26. PMID: 26613620. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26613620/. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Huston P, McFarlane B. Health benefits of tai chi: What is the evidence? Can Fam Physician. 2016 Nov;62(11):881-890. PMID: 28661865. https://www.cfp.ca/content/62/11/881. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Department of Veterans Affairs. Evidence Map of Acupuncture. 2014. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/acupuncture.pdf. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Department of Veterans Affairs. Evidence Map of Mindfulness. 2014. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/cam_mindfulness-REPORT.pdf. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Press Ganey. Protecting Market Share in the Era of Reform: Understanding Patient Loyalty in the Medical Practice Segment. White Paper. 2013. http://img.en25.com/Web/PressGaneyAssociatesInc/PerfInsights_PatientLoyalty_Nov2013.pdf?elq=a66e16008286435885d97352358aefd3. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Crocker, R.L., Grizzle, A.J., Hurwitz, J.T. et al. Integrative medicine primary care: assessing the practice model through patients’ experiences. BMC Complement Altern Med 17, 490 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-017-1996-5. Accessed 3/10/21.

- The Impact of Relationship-Based Care. South Central Foundation Nuka System of Care. https://scfnuka.com/impact-relationship-based-care/. Accessed 3/10/21.

- Myklebust M, Pradhan EK, Gorenflo D. An integrative medicine patient care model and evaluation of its outcomes: the University of Michigan experience. J Altern Complement Med. 2008 Sep;14(7):821-6. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0154. PMID:18721082. https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/63379/acm.2008.0154.pdf;sequence=1 . Accessed 7/15/21.

- Cover Commission. Creating Options for Veterans’ Expedited Recovery: Final Report. January 24, 2020. https://www.va.gov/COVER/docs/COVER-Commission-Final-Report-2020-01-24.PDF. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Sarnat RL, Winterstein J. Clinical and cost outcomes of an integrative medicine IPA. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 2004 Jun;27(5):336-347. DOI: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2004.04.007. https://cdn.ymaws.com/nebraskachiropractic.org/resource/resmgr/Docs/Clinical_and_Cost_Outcomes.pdf. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Pruitt Z, Emechebe N, Quast T, Taylor P, Bryant K. Expenditure Reductions Associated with a Social Service Referral Program. Popul Health Manag. 2018 Dec;21(6):469-476. doi: 10.1089/pop.2017.0199. Epub 2018 Apr 17. PMID: 29664702; PMCID: PMC6276598. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29664702/. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Jonk Y, Lawson K, O’Connor H, Riise KS, Eisenberg D, Dowd B, Kreitzer MJ. How effective is health coaching in reducing health services expenditures? Med Care. 2015 Feb;53(2):133-40. doi: 10.1097/ MLR.0000000000000287. PMID: 25588134. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25588134/. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Cherkin DC, Herman PM. Cognitive and Mind-Body Therapies for Chronic Low Back Pain and Neck Pain: Effectiveness and Value. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(4):556–557. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0113. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/articleabstract/2673371. Accessed 7/15/21.

- De Marchis E, Knox M, Hessler D, Willard-Grace R, Olayiwola JN, Peterson LE, Grumbach K, Gottlieb LM. Physician Burnout and Higher Clinic Capacity to Address Patients’ Social Needs. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019 Jan-Feb;32(1):69-78. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2019.01.180104. PMID: 30610144. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30610144/. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Wilkinson H, Whittington R, Perry L, Eames C. Examining the relationship between burnout and empathy in healthcare professionals: A systematic review. Burn Res. 2017 Sep;6:18-29. doi: 10.1016/j.burn.2017.06.003. PMID: 28868237; PMCID: PMC5534210. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28868237/. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Eby D, Ross L. Internationally Heralded Approaches to Population Health Driven by Alaska Native/American Indian/Native American Communities. Institute for Healthcare Improvement 8th annual National Forum, 2016. http://app.ihi.org/FacultyDocuments/Events/Event-2760/Presentation-14234/Document-11589/Presentation_L2_Internationally_Heralded_Approaches_to_Population_Health_driven_by_Alaska_NativeAmerican_IndianNative_American_Communities_Eby.pdf. Accessed 7/15/21.

- Finnegan J. Integrative medicine physicians say quality of life is better. Fierce Healthcare. August 22, 2017. https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/practices/doctorspracticing-integrative-medicine-say-quality-life-better.Accessed 7/15/21.

Topics: Integrative Health